Frontotemporal Dementia via the GRN Gene

Summary and Pricing

Test Method

Sequencing and CNV Detection via NextGen Sequencing using PG-Select Capture Probes| Test Code | Test Copy Genes | Test CPT Code | Gene CPT Codes Copy CPT Code | Base Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7061 | GRN | 81406 | 81406,81479 | $990 | Order Options and Pricing |

Pricing Comments

Testing run on PG-select capture probes includes CNV analysis for the gene(s) on the panel but does not permit the optional add on of exome-wide CNV analysis. Any of the NGS platforms allow reflex to other clinically relevant genes, up to whole exome or whole genome sequencing depending upon the base platform selected for the initial test.

An additional 25% charge will be applied to STAT orders. STAT orders are prioritized throughout the testing process.

This test is also offered via a custom panel (click here) on our exome or genome backbone which permits the optional add on of exome-wide CNV or genome-wide SV analysis.

Turnaround Time

3 weeks on average for standard orders or 2 weeks on average for STAT orders.

Please note: Once the testing process begins, an Estimated Report Date (ERD) range will be displayed in the portal. This is the most accurate prediction of when your report will be complete and may differ from the average TAT published on our website. About 85% of our tests will be reported within or before the ERD range. We will notify you of significant delays or holds which will impact the ERD. Learn more about turnaround times here.

Targeted Testing

For ordering sequencing of targeted known variants, go to our Targeted Variants page.

Clinical Features and Genetics

Clinical Features

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), previously referred to as Pick’s disease, is a clinically heterogeneous syndrome due to the progressive degeneration and atrophy of various regions of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Symptoms are insidious and begin usually during the fourth and sixth decades of life; although earlier and later onset have been documented (Snowden et al. 2002; Bruni et al. 2007 ). Two major forms, the behavioral-variant (FTD-bv) and the primary progressive aphasia (PPA), are recognized based on the site of onset of degeneration and the associated symptoms. In FTD-bv the degenerative process begins in the frontal lobes and results in personality changes and deterioration of social conducts. Most common behavioral changes are: disinhibition, apathy, deterioration of executive function, obsessive thoughts, compulsive behavior, and neglect of personal hygiene. In PPA the degenerative process begins in the temporal lobes. PPA is a language disorder that is further divided into two sub-forms: progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA) and semantic dementia (SD). PNFA is characterized by difficulty in verbal communications, word retrieval, and speech distortion. Reading, writing and spelling are also affected; while memory is relatively preserved. SD is characterized by the progressive impairment of word comprehension, object and face recognition, and loss of semantic memory. Reading and writing skills are relatively preserved (Gustafson et al. 1993). The clinical diagnosis of FTD is based on the combination of medical history, physical and neurological examination, brain imaging, and neuropsychological and psychiatric assessment (Neary et al. 1998; Snowden 2002; Rascovsky et al 2011; Mesulam 2001). FTD affects people worldwide, with a prevalence of up to 15 per 100,000 (Ratnavalli et al. 2002). It is the second most common dementia in people under the age of 65 years, after Alzheimer's disease, accounting for up to 20% of presenile dementia cases (Snowden et al. 2002).

Genetics

FTD is inherited in about 40% of cases (Rosso et al. 2003). In these families, the disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The remaining cases appear to be simplex with no known affected relatives. It is, however, unclear how many of the apparently sporadic cases are inherited with low penetrance (Cruts et al. 2006; Le Ber et al. 2007). FTD is genetically heterogeneous. Several genes have been implicated in the disorder: C9orf72, GRN, MAPT, CHMPEB, TARDBP, FUS and VCP. Pathogenic variants in the GRN gene account for up to 23 % of FTD familial cases and 5.8 % of simplex cases (Baker et al. 2006; Gass et al. 2006; Chen-Plotkin et al. 2011). About 120 different GRN pathogenic variants, distributed along the entire coding region of the gene, have been reported in patients with the various forms of FTD. Although the majority of variants are of the types that are expected to result in a truncated protein, missense variants that are predicted to result in amino acid substitutions have been documented (Human Gene Mutation Database; Cruts et al. 2006; van der Zee et al. 2007). There are no clear genotype-phenotype correlations. The same pathogenic variants result in various clinical presentations even within members of the same family, suggesting the involvement of genetic and environmental modifying factors (Hsiung and Feldman 2013). In addition to FTD, a homozygous truncating variant was reported to cause an adult form of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Smith et al. 2012). See also the description for Test #1909. The progranulin protein, also known as granulin, is a growth factor involved in various cellular functions, including neuronal survival (He and Bateman 2003). Its loss affects normal neurite outgrowth and branching (Gass et al. 2012).

Clinical Sensitivity - Sequencing with CNV PG-Select

Pathogenic variants in the GRN gene account for up to 23 % of FTD familial cases and 5.8 % of simplex cases (Baker et al. 2006; Gass et al. 200; Chen-Plotkin et al. 2011).

Testing Strategy

This test provides full coverage of all coding exons of the GRN gene, plus ~10 bases of flanking noncoding DNA. We define full coverage as >20X NGS reads or Sanger sequencing.

Indications for Test

All patients with symptoms and MRI findings suggestive of FTD-bv or PPA, as described (Neary 1998; Snowden 2002; Rascovsky et al 2011; Mesulam 2001).

All patients with symptoms and MRI findings suggestive of FTD-bv or PPA, as described (Neary 1998; Snowden 2002; Rascovsky et al 2011; Mesulam 2001).

Gene

| Official Gene Symbol | OMIM ID |

|---|---|

| GRN | 138945 |

| Inheritance | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Autosomal Dominant | AD |

| Autosomal Recessive | AR |

| X-Linked | XL |

| Mitochondrial | MT |

Disease

| Name | Inheritance | OMIM ID |

|---|---|---|

| Frontotemporal Dementia, Ubiquitin-Positive | AD | 607485 |

Related Tests

| Name |

|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease, Familial via the PSEN1 Gene |

| Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (Batten Disease) Panel |

Citations

- Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, Cannon A, Dwosh E, et al. 2006. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature 442: 916–919. PubMed ID: 16862116

- Bruni A.C. et al. 2007. Neurology. 69: 140-7. PubMed ID: 17620546

- Chen-Plotkin AS, Martinez-Lage M, Sleiman PMA, Hu W, Greene R, Wood EM, Bing S, Grossman M, Schellenberg GD, Hatanpaa KJ, Weiner MF, White CL, et al. 2011. Genetic and Clinical Features of Progranulin-Associated Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Archives of Neurology 68: 488. PubMed ID: 21482928

- Cruts M, Gijselinck I, Zee J van der, Engelborghs S, Wils H, Pirici D, Rademakers R, Vandenberghe R, Dermaut B, Martin J-J, Duijn C van, Peeters K, Sciot R, Santens P, De Pooter T, Mattheijssens M, Van den Broeck M, Cuijt I, Vennekens K, De Deyn PP, Kumar-Singh S, Van Broeckhoven C. 2006. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature 442: 920–924. PubMed ID: 16862115

- Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, Boeve B, Baker M, Adamson J, Crook R, Melquist S, Kuntz K, Petersen R, Josephs K, Pickering-Brown SM, et al. 2006. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15: 2988–3001. PubMed ID: 16950801

- Gass J, Lee WC, Cook C, Finch N, Stetler C, Jansen-West K, Lewis J, Link CD, Rademakers R, Nykjær A, Petrucelli L. 2012. Progranulin regulates neuronal outgrowth independent of Sortilin. Molecular Neurodegeneration 7: 33. PubMed ID: 22781549

- Gustafson L. 1993. Dementia. 4: 143-8. PubMed ID: 8401782

- He Z, Bateman A. 2003. Progranulin (granulin-epithelin precursor, PC-cell-derived growth factor, acrogranin) mediates tissue repair and tumorigenesis. J. Mol. Med. 81: 600–612. PubMed ID: 12928786

- Hsiung G-YR, Feldman HH. 2013. GRN-Related Frontotemporal Dementia. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong C-T, Smith RJ, and Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews(®), Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PubMed ID: 20301545

- Human Gene Mutation Database (Bio-base).

- Le Ber I, Zee J van der, Hannequin D, Gijselinck I, Campion D, Puel M, Laquerrière A, Pooter T De, Camuzat A, Broeck M Van den, Dubois B, Sellal F, Lacomblez L, Vercelletto M, Thomas-Antérion C, Michel BF, Golfier V, Didic M, Salachas F, Duyckaerts C, Cruts M, Verpillat P, Van Broeckhoven C, Brice A; French Research Network on FTD/FTD-MND. 2007. Progranulin null mutations in both sporadic and familial frontotemporal dementia. Human Mutation 28: 846–855. PubMed ID: 17436289

- Mesulam M.M. 2001. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 49: 425–432. PubMed ID: 11310619

- Neary D. et al. 1998. Neurology. 51: 1546-54. PubMed ID: 9855500

- Rascovsky K. et al. 2011. Brain : a Journal of Neurology. 134: 2456-77. PubMed ID: 21810890

- Ratnavalli E. et al. 2002. Neurology. 58: 1615-21. PubMed ID: 12058088

- Rosso S.M. et al. 2003. Brain : a Journal of Neurology. 126: 2016-22. PubMed ID: 12876142

- Smith KR, Damiano J, Franceschetti S, Carpenter S, Canafoglia L, Morbin M, Rossi G, Pareyson D, Mole SE, Staropoli JF, Sims KB, Lewis J, et al. 2012. Strikingly Different Clinicopathological Phenotypes Determined by Progranulin-Mutation Dosage. Am J Hum Genet 90: 1102–1107. PubMed ID: 22608501

- Snowden J.S. 2002. Frontotemporal dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry 180: 140-3. PubMed ID: 11823324

- van der Zee J, Ber I Le, Maurer-Stroh S, Engelborghs S, Gijselinck I, Camuzat A, Brouwers N, Vandenberghe R, Sleegers K, Hannequin D, Dermaut B, Schymkowitz J, et al. 2007. Mutations other than null mutations producing a pathogenic loss of progranulin in frontotemporal dementia. Human Mutation 28: 416–416. PubMed ID: 17345602

Ordering/Specimens

Ordering Options

We offer several options when ordering sequencing tests. For more information on these options, see our Ordering Instructions page. To view available options, click on the Order Options button within the test description.

myPrevent - Online Ordering

- The test can be added to your online orders in the Summary and Pricing section.

- Once the test has been added log in to myPrevent to fill out an online requisition form.

- PGnome sequencing panels can be ordered via the myPrevent portal only at this time.

Requisition Form

- A completed requisition form must accompany all specimens.

- Billing information along with specimen and shipping instructions are within the requisition form.

- All testing must be ordered by a qualified healthcare provider.

For Requisition Forms, visit our Forms page

If ordering a Duo or Trio test, the proband and all comparator samples are required to initiate testing. If we do not receive all required samples for the test ordered within 21 days, we will convert the order to the most effective testing strategy with the samples available. Prior authorization and/or billing in place may be impacted by a change in test code.

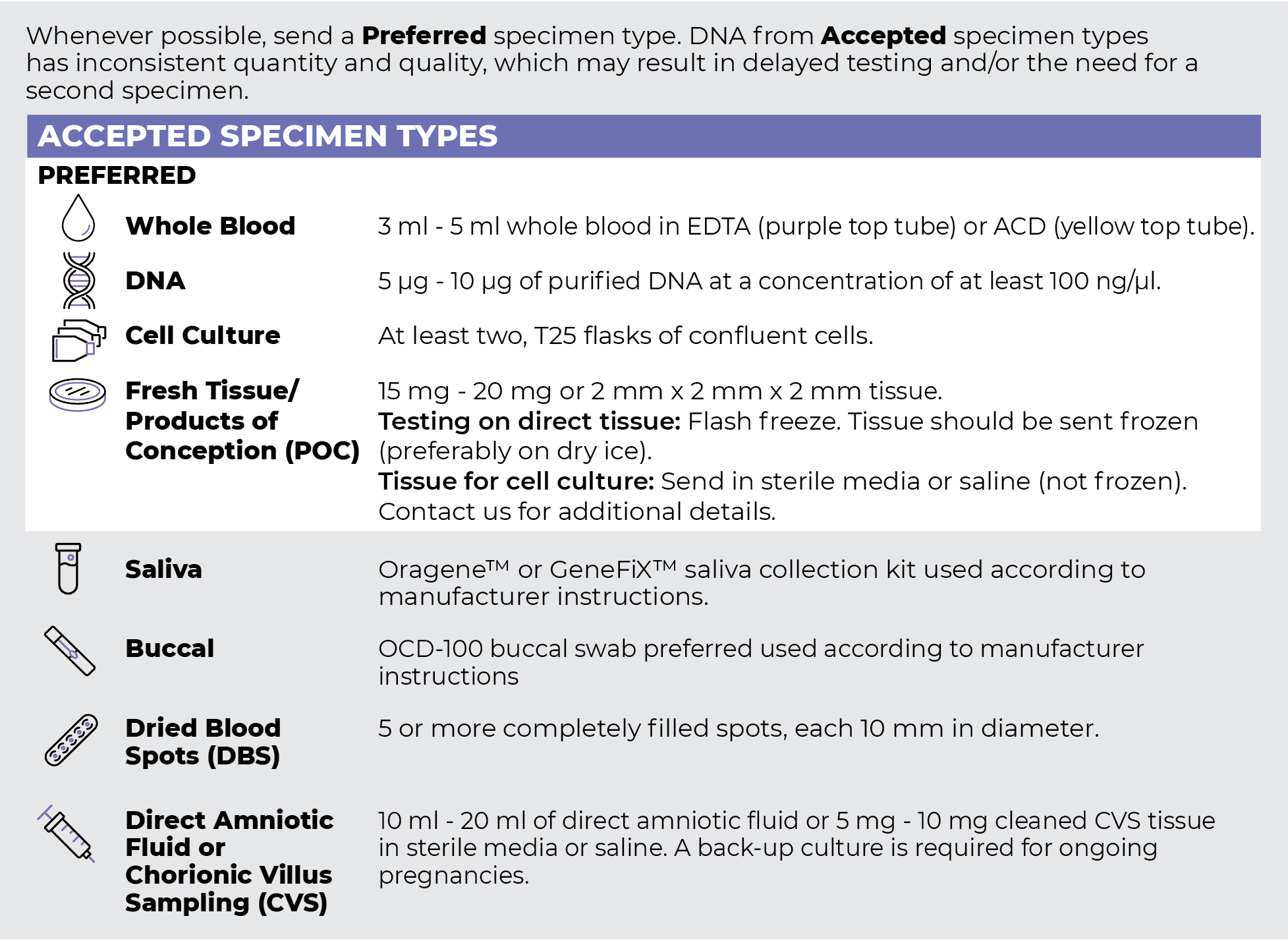

Specimen Types

Specimen Requirements and Shipping Details

ORDER OPTIONS

View Ordering Instructions1) Select Test Type

2) Select Additional Test Options

No Additional Test Options are available for this test.