Severe Combined Immunodeficiency/Omenn Syndrome via the DCLRE1C (ARTEMIS) Gene

Summary and Pricing

Test Method

Sequencing and CNV Detection via NextGen Sequencing using PG-Select Capture Probes| Test Code | Test Copy Genes | Test CPT Code | Gene CPT Codes Copy CPT Code | Base Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4589 | DCLRE1C | 81479 | 81479,81479 | $990 | Order Options and Pricing |

Pricing Comments

Testing run on PG-select capture probes includes CNV analysis for the gene(s) on the panel but does not permit the optional add on of exome-wide CNV analysis. Any of the NGS platforms allow reflex to other clinically relevant genes, up to whole exome or whole genome sequencing depending upon the base platform selected for the initial test.

An additional 25% charge will be applied to STAT orders. STAT orders are prioritized throughout the testing process.

This test is also offered via a custom panel (click here) on our exome or genome backbone which permits the optional add on of exome-wide CNV or genome-wide SV analysis.

Turnaround Time

3 weeks on average for standard orders or 2 weeks on average for STAT orders.

Please note: Once the testing process begins, an Estimated Report Date (ERD) range will be displayed in the portal. This is the most accurate prediction of when your report will be complete and may differ from the average TAT published on our website. About 85% of our tests will be reported within or before the ERD range. We will notify you of significant delays or holds which will impact the ERD. Learn more about turnaround times here.

Targeted Testing

For ordering sequencing of targeted known variants, go to our Targeted Variants page.

Clinical Features and Genetics

Clinical Features

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) encompasses a diverse group of rare, life-threatening disorders. While the true incidence of SCID is unknown, newborn screening studies suggest that 1 in 70,000 births are affected with a range of 1 in 40,000 to 100,000 (Fischer. 2000. PubMed ID: 11091267; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). SCID is caused by genetic defects that inhibit lymphocyte development and function, resulting in no T cell differentiation and abnormal development of B and natural killer (NK) lymphocytes (Fischer. 2000. PubMed ID: 11091267; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). The clinical features associated with SCID include recurrent and severe bacterial, viral, and fungal infections that begin in infancy (Fischer. 2000. PubMed ID: 11091267; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). To date, there are over 20 genes known to be associated with SCID (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Bousfiha et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226301; Picard et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226302; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275; Tangye et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 31953710). The majority of the genes are involved in autosomal recessive SCID; however IL2RG is associated with an X-linked form of the disease (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584). Patients with SCID due to pathogenic variants in DCLRE1C lack T and B cells while retaining normal NK cell levels (T-B-NK+ SCID; Bousfiha et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226301). Patients with this form of SCID are sensitive to ionizing radiation and chemotherapeutic agents (Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). Previous studies have shown that DCLRE1C pathogenic variants are a rare cause of SCID as compared to the other genetic causes (Lindegren et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14724556; Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19433858; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402; Dvorak et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 23818196; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334).

Classification of SCID may be subdivided based on B cell status and further subdivided based on NK cell status (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). Omenn Syndrome (OS), also known as leaky SCID, typically presents during the first year of life and is characterized by erythroderma, desquamation, eosinophilia, failure to thrive, lymphadenopathy and chronic diarrhea (Ege et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15731174). Patients with OS have limited B cells and elevated T cell levels with impaired function resulting in a distinct inflammatory phenotype (T+B-NK+ SCID). OS is due to hypomorphic variants predominantly in the RAG1 and RAG2 genes, but DCLRE1C and IL7R can also have causative variants (Villa et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 11908269; Ege et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15731174; Zago et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 24759676).

Regardless of the type of SCID, it is necessary to establish a genetic diagnosis for genetic counseling, prognostication, and optimization of treatment (Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). The recurrence risk and prognosis may vary depending on the underlying genetic cause of the deficiency. In general, the prognosis is poor if there is a delay in diagnosis and therapy. Early hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the most established treatment for patients with SCID (Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334).

Genetics

To date, over 20 genes causative for autosomal recessive forms of SCID, including DCLRE1C, have been identified (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Bousfiha et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226301; Picard et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226302; Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275; Tangye et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 31953710). Variants in IL2RG are causative for X-linked SCID and account for ~40-60% of all cases (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Fischer. 2000. PubMed ID: 11091267; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402). Pathogenic variants in ADA and IL7R account for 5-20% of all cases of SCID, while variants in all other genes, including DCLRE1C, account for ~10% of SCID (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Kalman et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14726805; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402). OS is also inherited in an autosomal recessive manner through variants in the RAG1, RAG2, DCLRE1C, or IL7R genes (Villa et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 11908269; Ege et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15731174; Zago et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 24759676).

Causative variants in SCID genes may be inherited from unaffected parents or may occur de novo in the patient. Studies analyzing newborns with SCID determined that only ~20% had a family history of immunodeficiency, while ~80% of cases lacked a positive family history (Chan and Puck. 2005. PubMed ID: 15696101; Puck. 2007. PubMed ID: 17931561; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334). Those with a lack of family history are a result of de novo variants and unknown carrier status. These studies analyzed SCID as a whole and did not break down the analysis into the different subtypes of SCID.

Historically, DCLRE1C pathogenic variants are rarely identified compared to other causes of SCID (Dvorak et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 23818196; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402). They are primarily located within exons 1-8, but have been reported throughout the entire coding region. Large deletions or nonsense variants, typically including exon 1, are causative for ~50% of DCLRE1C mediated SCID, while missense, splicing, small deletions, and small insertions/duplications make up the other half of causative variants in the DCLRE1 gene (Pannicke et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 19953608). Hypomorphic variants in DCLRE1C, typically missense, leading to impaired but not complete loss of protein function are associated with OS (Villa et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 11908269; Ege et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15731174).

Of note, a founder variant in DCLRE1C [c.597C>A (p.Tyr199*)] has been identified in the Native American population. This variant is estimated to occur at ~10% carrier rate and lead to SCID in ~1 in 2,000 births (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Li et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 12055248, Kalman et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14726805; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334).

The DCLRE1C gene encodes a DNA cross-link repair protein, commonly referred to as ARTEMIS. This protein allows completion of VDJ recombination required for T and B cell receptor assembly through non-homologous end repair of DNA (Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275). A deficiency, either complete or partial, of the ARTEMIS protein may lead to early arrest in the maturation of T cells and in the differentiation of B cells, resulting in the various forms of SCID (Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275).

Mouse models have been utilized to study DCLRE1C SCID. DLCRE1C knockout models, or models showing complete loss of DCLRE1C function, had a phenotype consistent with SCID with increased cellular ionizing radiation sensitivity and chromosomal instability in fibroblasts (Rooney et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 12504013; Li et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15699179). The phenotype of the knockout mouse model was partially corrected via bone marrow transplantation. In addition, the post-transplant immune system favored a T cell, rather than B cell, reconstitution which is similar to that observed in patients with SCID post-transplant (Li et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15699179). A mouse model harboring DCLRE1C hypomorphic variants, rather than a complete knockout, was created to study OS. This model had a phenotype that was distinct from the DCLRE1C knockout mouse models and had an increase in aberrant intra- and interchromosomal VDJ joining events (Jacobs et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21147755).

Clinical Sensitivity - Sequencing with CNV PG-Select

Pathogenic variants in DCLRE1C are rarely identified compared to other known causes of SCID (Dvorak et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 23818196; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402). DCLRE1C pathogenic variants have been identified in ~1% of SCID cases (outside of the Native American population) (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Kalman et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14726805; Lindegren et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14724556; Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19433858; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402; Dvorak et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 23818196; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334). In the Native American population a DCLRE1C founder variant has been estimated to occur at ~10% carrier rate and lead to SCID in ~1 in 2,000 births (Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584; Li et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 12055248, Kalman et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14726805; Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334).

The clinical sensitivity of DCLRE1C variants in regards to OS is difficult to estimate. The incidence of OS is rare as compared to SCID. Previous analyses of the causative genetic variants in patients with various types of SCID determined that 0-8% of their SCID cohorts had OS (Lindegren et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14724556; Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19433858; Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402). However, the specific genetic variants were not reported.

Testing Strategy

This test is performed using Next-Gen sequencing with additional Sanger sequencing as necessary.

This test provides full coverage of all coding exons of the DCLRE1C gene plus 10 bases flanking noncoding DNA in all available transcripts in addition to non-coding regions in which pathogenic variants have been identified at PreventionGenetics or reported elsewhere. We define full coverage as ≥20X NGS reads or Sanger sequencing.

Since this test is performed using exome capture probes, a reflex to any of our exome based tests is available (PGxome, PGxome Custom Panels.

Indications for Test

Candidates for testing include those with severe lymphopenia and lack of adaptive immunity. Ideal candidates have a T-B-NK+ immunophenotype, which is consistent with SCID via DCLRE1C, or clinical features indicating OS. Testing is especially recommended for newborns identified via newborn screening for SCID using T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) screening. Carrier testing is available for individuals with a family history of the disease and for the reproductive partners of individuals who carry pathogenic variants in DCLRE1C.

Candidates for testing include those with severe lymphopenia and lack of adaptive immunity. Ideal candidates have a T-B-NK+ immunophenotype, which is consistent with SCID via DCLRE1C, or clinical features indicating OS. Testing is especially recommended for newborns identified via newborn screening for SCID using T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) screening. Carrier testing is available for individuals with a family history of the disease and for the reproductive partners of individuals who carry pathogenic variants in DCLRE1C.

Gene

| Official Gene Symbol | OMIM ID |

|---|---|

| DCLRE1C | 605988 |

| Inheritance | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Autosomal Dominant | AD |

| Autosomal Recessive | AR |

| X-Linked | XL |

| Mitochondrial | MT |

Diseases

| Name | Inheritance | OMIM ID |

|---|---|---|

| Omenn Syndrome | AR | 603554 |

| Severe Combined Immunodeficiency With Sensitivity To Ionizing Radiation | AR | 602450 |

Related Test

| Name |

|---|

| Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) Panel |

Citations

- Allenspach et al. 1993. PubMed ID: 20301584

- Bousfiha et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226301

- Chan and Puck. 2005. PubMed ID: 15696101

- Chan et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21035402

- Dvorak et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 23818196

- Ege et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15731174

- Fischer. 2000. PubMed ID: 11091267

- Jacobs et al. 2011. PubMed ID: 21147755

- Kalman et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14726805

- Kumrah et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 32181275

- Kwan et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 25138334

- Li et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 12055248

- Li et al. 2005. PubMed ID: 15699179

- Lindegren et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 14724556

- Pannicke et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 19953608

- Picard et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29226302

- Puck. 2007. PubMed ID: 17931561

- Rooney et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 12504013

- Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19433858

- Tangye et al. 2020. PubMed ID: 31953710

- Villa et al. 2002. PubMed ID: 11908269

- Zago et al. 2014. PubMed ID: 24759676

Ordering/Specimens

Ordering Options

We offer several options when ordering sequencing tests. For more information on these options, see our Ordering Instructions page. To view available options, click on the Order Options button within the test description.

myPrevent - Online Ordering

- The test can be added to your online orders in the Summary and Pricing section.

- Once the test has been added log in to myPrevent to fill out an online requisition form.

- PGnome sequencing panels can be ordered via the myPrevent portal only at this time.

Requisition Form

- A completed requisition form must accompany all specimens.

- Billing information along with specimen and shipping instructions are within the requisition form.

- All testing must be ordered by a qualified healthcare provider.

For Requisition Forms, visit our Forms page

If ordering a Duo or Trio test, the proband and all comparator samples are required to initiate testing. If we do not receive all required samples for the test ordered within 21 days, we will convert the order to the most effective testing strategy with the samples available. Prior authorization and/or billing in place may be impacted by a change in test code.

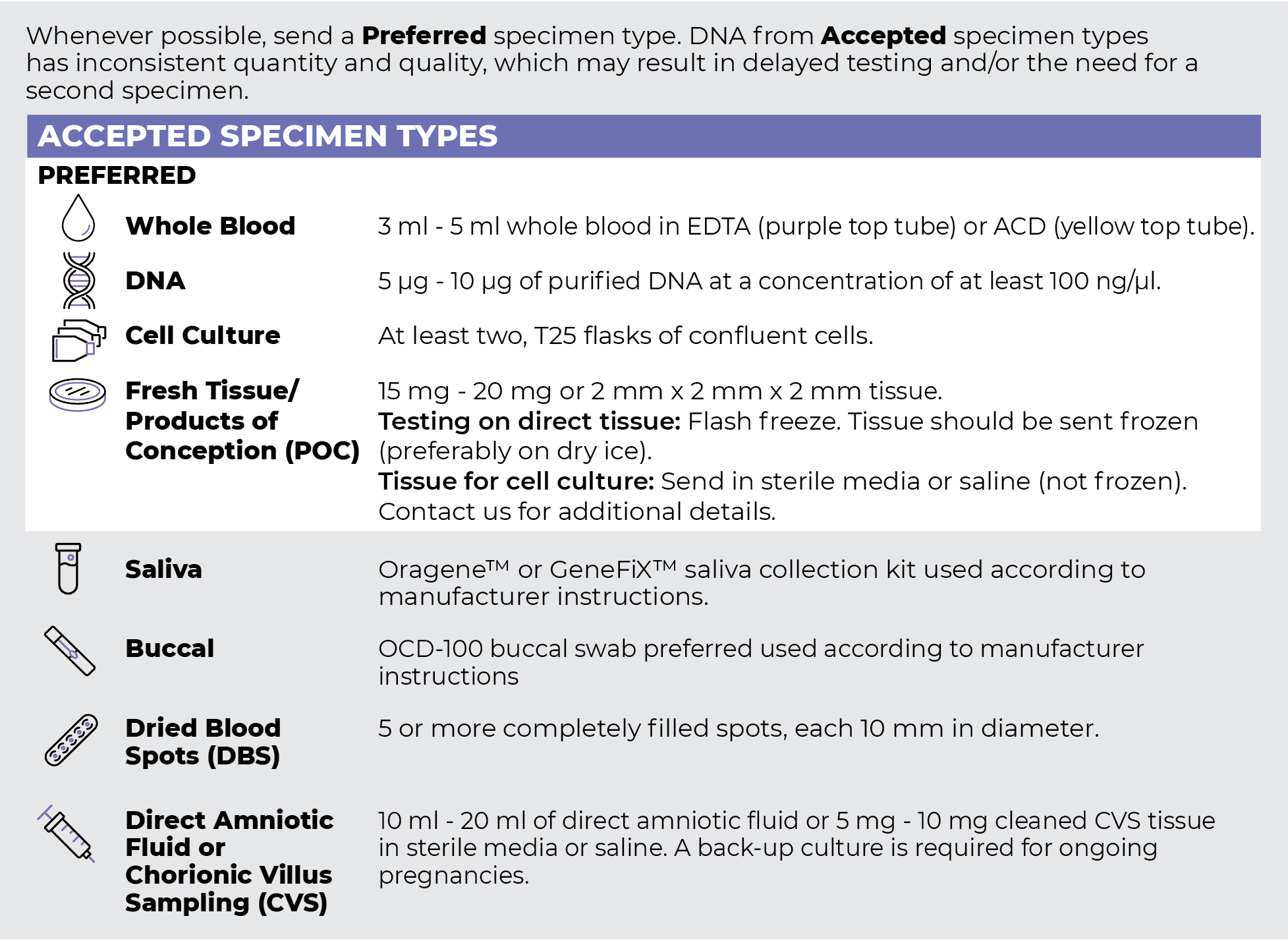

Specimen Types

Specimen Requirements and Shipping Details

ORDER OPTIONS

View Ordering Instructions1) Select Test Type

2) Select Additional Test Options

No Additional Test Options are available for this test.