Pancreatic Cancer Panel

Summary and Pricing

Test Method

Sequencing and CNV Detection via NextGen Sequencing using PG-Select Capture Probes| Test Code | Test Copy Genes | Panel CPT Code | Gene CPT Codes Copy CPT Code | Base Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5461 | Genes x (18) | 81479 | 81162(x1), 81201(x1), 81203(x1), 81292(x1), 81294(x1), 81295(x1), 81297(x1), 81298(x1), 81300(x1), 81307(x1), 81317(x1), 81319(x1), 81403(x2), 81404(x3), 81405(x2), 81408(x1), 81479(x13) | $990 | Order Options and Pricing |

Pricing Comments

Testing run on PG-select capture probes includes CNV analysis for the gene(s) on the panel but does not permit the optional add on of exome-wide CNV analysis. Any of the NGS platforms allow reflex to other clinically relevant genes, up to whole exome or whole genome sequencing depending upon the base platform selected for the initial test.

An additional 25% charge will be applied to STAT orders. STAT orders are prioritized throughout the testing process.

This test is also offered via a custom panel (click here) on our exome or genome backbone which permits the optional add on of exome-wide CNV or genome-wide SV analysis.

Turnaround Time

3 weeks on average for standard orders or 2 weeks on average for STAT orders.

Please note: Once the testing process begins, an Estimated Report Date (ERD) range will be displayed in the portal. This is the most accurate prediction of when your report will be complete and may differ from the average TAT published on our website. About 85% of our tests will be reported within or before the ERD range. We will notify you of significant delays or holds which will impact the ERD. Learn more about turnaround times here.

Targeted Testing

For ordering sequencing of targeted known variants, go to our Targeted Variants page.

Clinical Features and Genetics

Clinical Features

Familial inheritance has been estimated to occur in 5-10% of pancreatic cancer cases, and individuals with a family history have a greater risk of developing pancreatic cancer with each affected family member (Axilbund and Wiley. 2012. PubMed ID: 22846737). Individuals with either two or more first degree relatives with pancreatic cancer or three or more relatives of any degree with pancreatic cancer are considered to have familial pancreatic cancer (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588). Hereditary pancreatic cancer patients often show earlier ages of diagnosis compared to those with sporadic pancreatic cancer, and individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry have a higher risk to develop familial pancreatic cancer (Matsubayashi. 2011. PubMed ID: 21847571).

Even though no specific gene explains most cases of familial pancreatic cancer, affected individuals may have pathogenic variants in genes that are causative for other cancer syndromes. The syndromes that have pancreatic cancer as a clinical feature include familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC), Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Lynch syndrome, melanoma predisposition, and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Heterozygous carriers of pathogenic variants in genes causative for ataxia-telangiectasia and Fanconi anemia have also been found to have increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer (Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834).

Genetics

APC: Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline pathogenic variants in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. More than 1,200 pathogenic variants have been reported in APC (Human Gene Mutation Database), and >90% are nonsense or frameshift pathogenic variants that are predicted to result in a dysfunctional, truncated protein product (Nagase and Nakamura. 1993. PubMed ID: 8111410). Germline pathogenic variants are spread throughout the coding region (Beroud and Soussi. 1996. PubMed ID: 8594558). Several pathogenic variants have also been documented in the promoter, 3’ untranslated region (UTR), and deep intronic regions (Heinimann et al. 2001. PubMed ID: 11606402; Rosa et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19279422). Severe FAP (more than 1,000 polyps) typically occurs in patients with pathogenic variants between codons 1250 and 1464 (Caspari et al. 1994. PubMed ID: 7906810). In contrast, patients with attenuated FAP (fewer than 100 colorectal polyps) usually have pathogenic variants at the very 5’ and 3’ ends of the gene, or in an alternatively spliced region of exon 9 (Young et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9603437; Soravia et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9585611). Congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is limited to patients with pathogenic variants between codons 457 and 1444 (Caspari et al. 1995. PubMed ID: 7795585). Two missense variants, p.Ile1307Lys and p.Glu1317Lys (commonly found in Ashkenazi Jewish populations), predispose carriers to multiple colorectal adenomas (generally less than 100) and carcinoma, but with low and variable penetrance (Frayling et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9724771). The risk of developing pancreatic cancer in individuals with an APC pathogenic variant is <5% (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588).

ATM: Ataxia-telangiectasia is an autosomal recessive disorder that is caused by pathogenic variants in the ATM gene. ATM encodes a serine protein kinase (ATM) that is involved in DNA repair via phosphorylation of downstream proteins. It senses double-stranded DNA breaks, coordinates cell-cycle checkpoints prior to repair, and recruits repair proteins to damaged DNA sites (Taylor et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 15279810). Pathogenic variants in ATM result in defective checkpoint cycling. Over 500 private causative variants are described with no common hot spots. In North America, most affected individuals are compound heterozygotes for two ATM pathogenic variants. However, founder ATM pathogenic variants have been observed in several populations (Gatti. 2010. PubMed ID: 20301790). Heterozygous carriers of single pathogenic variants in ATM may be at increased risk for pancreatic cancer (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588; Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834).

BRCA1/BRCA2: Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. BRCA1 is a tumor suppressor gene that is involved in cellular processes including DNA damage repair, cell cycle progression, gene transcription, and ubiquitination. BRCA2 is a tumor suppressor gene that along with RAD51 has a large role in DNA repair processes and genome stability. Most pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are private pathogenic variants which are observed in a single family or in a small number of families. Three pathogenic variants in the BRCA genes are commonly found in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals: BRCA1 c.68_69delAG, BRCA1 c.5266dupC, and BRCA2 c.5946delT; the coexistence of more than one founder pathogenic variant has been reported in some Ashkenazi Jewish families. Most BRCA pathogenic variants are inherited from a parent who may or may not have been affected with HBOC due to incomplete penetrance of the pathogenic variant, gender, and other factors (Petrucelli et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 20301425). Most pathogenic variants are predicted to result in truncated BRCA1 or BRCA2 proteins.

CDKN2A/CDK4: Melanoma predisposition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The strongest genetic risk for the development of melanoma results from heritable alterations in the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene. The CDKN2A gene is a tumor suppressor gene, and its protein products help regulate cell division and apoptosis (Nelson and Tsao. 2009. PubMed ID: 19095153). CDKN2A encodes two separate but related proteins, p16/INK4a and p14/ARF, by using two different promoters. The p16/INK4a protein is produced from a transcript generated from exons 1α, 2, and 3, whereas p14ARF is produced, using an alternative reading frame, from a transcript comprising exons 1β, 2, and 3 (Lin and Fisher. 2007. PubMed ID: 17314970). The function of the p16/INK4a protein is to inhibit CDK4/6 protein-mediated phosphorylation of the Rb (retinoblastoma) tumor suppressor protein; dephosphorylated Rb is the active state. Mutated p16/INK4a leads to phosphorylation of Rb, which in turn results in release of the bound transcription factor E2F. This allows the cell to undergo unregulated cell division leading to the development of melanoma. p14/ARF exerts its regulation of cell division through its indirect interaction with the p53 protein. p14/ARF binds to and inhibits the HDM2 protein, which functions to ubiquitinate proteins and target them for degradation. Pathogenic variants in p14/ARF abrogate binding to HDM2. As a result, HDM2 is released and increases ubiquitination of p53, leading to increased destruction of this tumor suppressor. The main functions of p53 are to sense genetic damage to allow pause for DNA repair and to activate cellular apoptosis. Thus, the decreased levels of p53 associated with mutations in p14/ARF lead to genetic instability and to a higher risk of melanoma in individuals with CDKN2A pathogenic variants (Lin and Fisher. 2007. PubMed ID: 17314970).

Families with mutated p14/ARF proteins also have an increase in neural system tumors in addition to melanoma (Nelson and Tsao. 2009. PubMed ID: 19095153). CDKN2A causative variants reported to date include mostly missense pathogenic variants; however, nonsense, splicing, small insertions and deletions, regulatory, and gross insertions and deletions have also been reported (Human Gene Mutation Database). The co-occurrence of melanoma and pancreatic cancer is an important indicator of a CDKN2A pathogenic variant. The risk of developing pancreatic cancer in melanoma predisposition syndrome is about 17% (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588). Melanoma patients with pathogenic variants in the related gene CDK4 may also have an increased risk for pancreatic cancer (Goldstein et al. 2006. PubMed ID: 17047042; Vasen et al. 2000. PubMed ID: 10956390).

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and EPCAM: Pathogenic variants in the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and EPCAM genes cause Lynch syndrome, which can include pancreatic cancer. Most of these genes are involved in mismatch repair. Pathogenic variants result in defective DNA repair, which leads to cancer (Bujanda et al. 2017. PubMed ID: 29151953). The risk of developing pancreatic cancer in Lynch syndrome is <5% (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588). Pancreatic tumors in Lynch syndrome tend to have a medullary appearance and present with microsatellite instability (Grover and Syngal. 2010. PubMed ID: 20727885). These patients tend to have a better prognosis in comparison to individuals with conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (Shi et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19260742).

PALB2: Homozygous pathogenic variants of the PALB2 gene have been shown to be causative for Fanconi anemia. The PALB2 gene acts as a tumor suppressor and colocalizes with the BRCA2 protein (Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834). Heterozygous pathogenic variants in the PALB2 gene confer susceptibility to familial pancreatic cancer (Jones et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19264984; Slater et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 20412113).

PALLD: PALLD encodes a component of the cytoskeleton, which is involved in controlling cell shape and motility. A missense variant in PALLD has been reported to segregate in a family with pancreatic cancer (Pogue-Geile et al. 2006. PubMed ID: 17194196). However, in other familial pancreatic cancer studies PALLD variants were not observed (Klein et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19336541; Ghiorzo et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22368299).

STK11: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is caused by heterozygous germline pathogenic variants in the tumor suppressor gene STK11. STK11, also called LKB1, encodes a serine/threonine kinase that inhibits cellular proliferation by promoting cell-cycle arrest (Tiainen et al. 1999. PubMed ID: 10430928). Second hit pathogenic variants in STK11 ultimately lead to unfettered growth and tumorigenesis. Pathogenic variants have been described throughout the STK11 gene (Human Gene Mutation Database). Most (80%) are truncating pathogenic variants (frameshift, nonsense, splice-site, or exonic deletions) that result in early translation termination (Hearle. 2006. PubMed ID: 16707622). The remaining pathogenic variants are missense or in-frame deletions. Large genomic deletions in STK11 have also been described. Those with PJS can have a lifetime risk for pancreatic cancer of 36% (Grover and Syngal. 2010. PubMed ID: 20727885). Individuals with STK11 pathogenic variants are predisposed to intraductal papillary mucincous neoplasms (Shi et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19260742).

TP53: Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and caused by heterozygous germline pathogenic variants in the TP53 gene (Malkin et. al. 1990. PubMed ID: 1978757; Srivastava et al. 1990. PubMed ID: 2259385). TP53 encodes the often-studied cellular tumor p53 antigen (Soussi. 2010. PubMed ID: 20930848). p53 is a ubiquitously expressed DNA-binding protein that plays a major role in the regulation of cell division, DNA repair, programmed cell death, and metabolism. More than 200 pathogenic variations have been reported throughout the TP53 gene, and nearly all are detectable by DNA sequencing (Human Gene Mutation Database). Gross deletions encompassing one or more exons of the TP53 gene have been described, but these account for less than 1% of all LFS patients. The lifetime risk of developing cancer for carriers of TP53 pathogenic variants has been estimated to be 73% for men and nearly 100% for women (Chompret et al. 2000. PubMed ID: 10864200). Li-Fraumeni syndrome is responsible for multiple cancers, including pancreatic cancer.

VHL: Heterozygous VHL pathogenic variants cause Von Hippel-Lindau disease, which is associated with a specific type of pancreatic cancer (pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor). The VHL gene is a tumor suppressor gene that plays a role in transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional gene expression, extracellular matrix formation, apoptosis, and ubiquitinylation (Roberts and Ohh. 2008. PubMed ID: 18043261).

FANCA: The FANCA gene encodes a protein that is part of a nuclear core complex that regulates monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 and FANCI proteins (ID complex) during S-phase and after exposure to DNA crosslinking agents (Moldovan and D'Andrea. 2009. PubMed ID: 19686080). Pathogenic variants in FANCA have been associated with autosomal recessive Fanconi anemia, complement group A. Fanconi anemia is a highly heterogeneous disorder. Association with other cancer types has also been reported, including pancreatic cancer (Zhan et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 30113427).

RABL3: The biological function of RABL3 is largely unknown, but evidence suggests it may have a role in regulation of cancer cell proliferation and motility (Li et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 20596630). At least one heterozygous variant in RABL3 has been reported to co-segregate with pancreatic cancer and other cancer types in a multigenerational family (Nissim et al. 2019. PubMed ID: 31406347).

Clinical Sensitivity - Sequencing with CNV PG-Select

ATM: Pathogenic ATM heterozygous variants in familial pancreatic cancer can be observed in up to 5% of affected individuals (Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588; Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834).

BRCA1 and BRCA2: Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have recently been reported in 1.2% and 3.7% of affected individuals, respectively, in a study of familial pancreatic cancer (Zhen et al. 2015. PubMed ID: 25356972).

CDKN2A: Pathogenic variants in CDKN2A were found in 2.5% of affected individuals with familial pancreatic cancer (Zhen et al. 2015. PubMed ID: 25356972).

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and EPCAM: One large study showed that 21% of families with Lynch syndrome had at least one case of pancreatic cancer (Kastrinos et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19861671).

PALB2: Pathogenic variants in the PALB2 gene may account for familial pancreatic cancer in up to 0.6-5% of cases (Axilbund and Wiley. 2012. PubMed ID: 22846737; Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588; Zhen et al. 2015. PubMed ID: 25356972).

The clinical sensitivity for pancreatic cancer caused by pathogenic variants in APC, CDK4, FANCA, PALLD, RABL3, STK11, TP53, and VHL is not known, but pancreatic cancer has been reported in syndromes resulting from pathogenic variants in these genes (Pogue-Geile et al. 2006. PubMed ID: 17194196; Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834; Das and Early. 2017. PubMed ID: 28879469; Matsubayashi et al. 2017. PubMed ID: 28246467; Nissim et al. 2019. PubMed ID: 31406347; Zhan et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 30113427).

Testing Strategy

This test is performed using Next-Gen sequencing with additional Sanger sequencing as necessary.

This panel typically provides 99.96% coverage of all coding exons of the genes plus 10 bases of flanking noncoding DNA in all available transcripts along with other non-coding regions in which pathogenic variants have been identified at PreventionGenetics or reported elsewhere. We define coverage as ≥20X NGS reads or Sanger sequencing.

DNA analysis of the PMS2 gene is complicated due to the presence of several pseudogenes. One particular pseudogene, PMS2CL, has high sequence similarity to PMS2 exons 11 to 15 (Blount et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 29286535). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) based copy number variant (CNV) analysis can detect deletions and duplications involving exons 1 to 10 of PMS2 but has less sensitivity for exons 11 through 15. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) can detect deletions and duplications involving PMS2 exons 1 to 15. Of note, PMS2 MLPA is not typically included in this test but can be ordered separately using test code 6062, if desired.

Indications for Test

This test is suitable for individuals with a clinical history of familial pancreatic cancers or who present with an autosomal dominant disorder that includes pancreatic cancer. This test especially aids in a differential diagnosis of similar phenotypes, rules out particular syndromes, and provides analysis of multiple genes simultaneously. Individuals with or without a family history of pancreatic tumors that are early onset (<50 years) could be assessed with this panel. This test is specifically designed for heritable germline mutations and is not appropriate for the detection of somatic mutations in tumor tissue.

This test is suitable for individuals with a clinical history of familial pancreatic cancers or who present with an autosomal dominant disorder that includes pancreatic cancer. This test especially aids in a differential diagnosis of similar phenotypes, rules out particular syndromes, and provides analysis of multiple genes simultaneously. Individuals with or without a family history of pancreatic tumors that are early onset (<50 years) could be assessed with this panel. This test is specifically designed for heritable germline mutations and is not appropriate for the detection of somatic mutations in tumor tissue.

Genes

| Official Gene Symbol | OMIM ID |

|---|---|

| APC | 611731 |

| ATM | 607585 |

| BRCA1 | 113705 |

| BRCA2 | 600185 |

| CDK4 | 123829 |

| CDKN2A | 600160 |

| EPCAM | 185535 |

| FANCA | 607139 |

| MLH1 | 120436 |

| MSH2 | 609309 |

| MSH6 | 600678 |

| PALB2 | 610355 |

| PALLD | 608092 |

| PMS2 | 600259 |

| RABL3 | 0 |

| STK11 | 602216 |

| TP53 | 191170 |

| VHL | 608537 |

| Inheritance | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Autosomal Dominant | AD |

| Autosomal Recessive | AR |

| X-Linked | XL |

| Mitochondrial | MT |

Diseases

Related Test

| Name |

|---|

| PGxome® |

| Hereditary Colorectal Cancer and Polyposis Panel |

Citations

- Axilbund and Wiley. 2012. PubMed ID: 22846737

- Bartsch et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22664588

- Béroud and Soussi. 1996. PubMed ID: 8594558

- Bujanda et al. 2017. PubMed ID: 29151953

- Caspari et al. 1994. PubMed ID: 7906810

- Caspari et al. 1995. PubMed ID: 7795585

- Chompret et al. 2000. PubMed ID: 10864200

- Das and Early. 2017. PubMed ID: 28879469

- Frayling et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9724771

- Gatti. 2010. PubMed ID: 20301790

- Ghiorzo et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 22368299

- Goldstein et al. 2006. PubMed ID: 17047042

- Grover and Syngal. 2010. PubMed ID: 20727885

- Hearle. 2006. PubMed ID: 16707622

- Heinimann et al. 2001. PubMed ID: 11606402

- Human Gene Mutation Database (Bio-base).

- Jones et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19264984

- Kastrinos et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19861671

- Klein et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19336541

- Li et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 20596630

- Lin and Fisher. 2007. PubMed ID: 17314970

- Malkin et.al. 1990. PubMed ID: 1978757

- Matsubayashi et al. 2017. PubMed ID: 28246467

- Matsubayashi. 2011. PubMed ID: 21847571

- Moldovan and D'Andrea. 2009. PubMed ID: 19686080

- Nagase and Nakamura. 1993. PubMed ID: 8111410

- Nelson and Tsao. 2009. PubMed ID: 19095153

- Nissim et al. 2019. PubMed ID: 31406347

- Petrucelli et al. 2013. PubMed ID: 20301425

- Pogue-Geile et al. 2006. PubMed ID: 17194196

- Roberts and Ohh. 2008. PubMed ID: 18043261

- Rosa et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19279422

- Shi et al. 2009. PubMed ID: 19260742

- Slater et al. 2010. PubMed ID: 20412113

- Solomon et al. 2012. PubMed ID: 23187834

- Soravia et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9585611

- Soussi. 2010. PubMed ID: 20930848

- Srivastava et al. 1990. PubMed ID: 2259385

- Taylor et al. 2004. PubMed ID: 15279810

- Tiainen et al. 1999. PubMed ID: 10430928

- Vasen et al. 2000. PubMed ID: 10956390

- Young et al. 1998. PubMed ID: 9603437

- Zhan et al. 2018. PubMed ID: 30113427

- Zhen et al. 2015. PubMed ID: 25356972

Ordering/Specimens

Ordering Options

We offer several options when ordering sequencing tests. For more information on these options, see our Ordering Instructions page. To view available options, click on the Order Options button within the test description.

myPrevent - Online Ordering

- The test can be added to your online orders in the Summary and Pricing section.

- Once the test has been added log in to myPrevent to fill out an online requisition form.

- PGnome sequencing panels can be ordered via the myPrevent portal only at this time.

Requisition Form

- A completed requisition form must accompany all specimens.

- Billing information along with specimen and shipping instructions are within the requisition form.

- All testing must be ordered by a qualified healthcare provider.

For Requisition Forms, visit our Forms page

If ordering a Duo or Trio test, the proband and all comparator samples are required to initiate testing. If we do not receive all required samples for the test ordered within 21 days, we will convert the order to the most effective testing strategy with the samples available. Prior authorization and/or billing in place may be impacted by a change in test code.

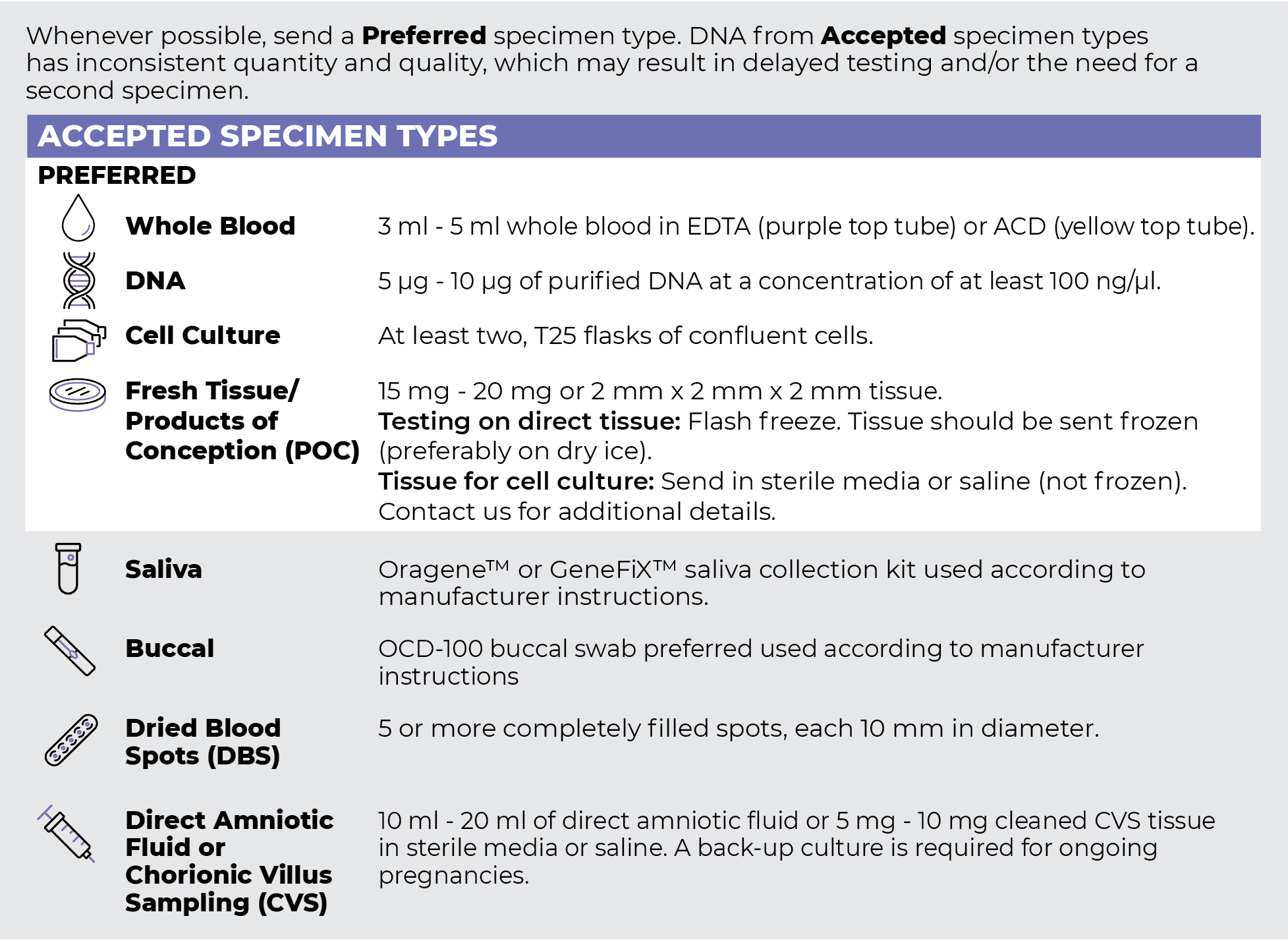

Specimen Types

Specimen Requirements and Shipping Details

ORDER OPTIONS

View Ordering Instructions1) Select Test Type

2) Select Additional Test Options

No Additional Test Options are available for this test.